Understanding Childhood Obesity as a Chronic Disease

Childhood obesity is often misunderstood, with many believing it results simply from individual choices or parenting practices. This misconception can foster a culture of blame and stigma. In reality, obesity is a complex health condition influenced by biological, environmental, and social factors. In this article, we explore why childhood obesity should be recognised and treated as a disease, and how greater understanding can help reduce stigma while supporting the development of more effective, compassionate approaches to prevention and care.

Defining Childhood Obesity as a Disease

When discussing why childhood obesity should be defined as a disease, it is important to first understand what is meant by the term disease.

The definition of disease is:

“Human disease is defined as an impairment of the healthy state of the human body that interrupts or modifies its vital functions.”1

Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic2 was published in 1998 by the World Health Organization, following consultation with the international Obesity Taskforce. In this document, obesity was described as a ‘complex’, ‘incompletely understood’ ‘serious and chronic’ disease which was part of a cluster of non-communicable diseases that required prevention and management strategies at both individual and societal levels.

It was also in 1998, when the National Institute of Health (NIH) designated obesity as a chronic disease3. This recognition led to greater research efforts and an evolving understanding of the role of the social determinants of health alongside clearer evidence of associated comorbidities. This helped the scientific and medical community appreciate the complexity of risk, diagnosis, and the necessity for appropriate treatment.

World Obesity Federation later published their position statement recognising obesity as a disease in 2017 as a review article written by several expert advisors4. This added to the growing international consensus that obesity should be recognised and treated as a disease.

Several leading authorities now define obesity as a disease in both adults and children.

“A chronic complex disease defined by excessive fat deposits that can impair health. Obesity can lead to increased risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, it can affect bone health and reproduction, it increases the risk of certain cancers. Obesity influences the quality of living, such as sleeping or moving.”5

The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) also argues obesity should be defined as a chronic disease, stating:

“Obesity is an adiposity-based chronic disease.. that profoundly impacts both physical and mental health. It is a highly prevalent and deeply stigmatised non-communicable disease (NCD), affecting virtually every system in the body.”6

The need for clinicians in paediatric care to develop knowledge and skills in the diagnosis and treatment of obesity has therefore become more pressing. Guidelines from across the globe, such as those from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)6 and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)8, reinforce this by strengthening the clinical framework around obesity, while emphasising comprehensive care rather than blame.

Similarly, the European Association for the Study of Obesity’s Childhood Obesity Task Force (COFT)9 has stressed that recognising childhood obesity as a chronic disease is essential for improving diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. This perspective helps shift the focus away from personal responsibility towards compassionate, evidence-based care.

By understanding obesity as a complex, chronic and relapsing condition rather than a lifestyle choice, healthcare systems can intervene earlier and more effectively, helping to prevent serious complications and reduce stigma.

Obesity as a Disease

From a medical perspective, obesity is recognised as a chronic, long-term disease. It happens when the body stores excess fat in ways that disrupt normal functioning and harm health. This is not about appearance or body size; the concern is how fat tissue affects important processes inside the body.

Obesity is complex and multifactorial. It develops through an interaction of genetics, biology, environment, and behaviour. For example, the body has systems that regulate appetite, metabolism, and how energy is stored. In obesity, these systems can become dysregulated, making it much harder for individuals to regulate weight on their own. This is why obesity often persists over time and can return even after weight loss and is often therefore a relapsing condition.

Because obesity affects many parts of the body, it increases the risk of other health conditions such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, certain cancers, and musculoskeletal problems. But equally important is the impact on daily life: it can affect sleep, energy levels, mobility, and mental well-being.

Recognising obesity as a disease helps ensure that it is approached with the same seriousness, compassion, and professional care as any other chronic health condition. It shifts the focus from blame to understanding, and from quick fixes to sustained, evidence-based support.

Why Treating Obesity as a Disease Is Important

Leading health organisations across the world consistently recognise obesity as a disease, highlighting the need for medical recognition, reduced stigma, early intervention, and systemic change. There are several benefits to taking this approach:

1. Improved diagnosis and treatment

1. Improved diagnosis and treatment

Classifying obesity as a disease frames it as a medical condition requiring diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment, rather than just lifestyle advice alone.

2. Promotes early intervention

2. Promotes early intervention

Recognising obesity as a disease allows healthcare systems to identify and intervene earlier, preventing progression and complications.

3. Reduces stigma and blame

3. Reduces stigma and blame

By acknowledging obesity as a condition with biological, environmental, and social drivers, the “choice” narrative is weakened, helping reduce stigma and discrimination.

4. Opens access to healthcare and insurance coverage

4. Opens access to healthcare and insurance coverage

Disease classification legitimises the need for medical care, resources, and, in some countries, insurance coverage for treatment.

5. Supports policy and systems change

5. Supports policy and systems change

Framing obesity as a disease helps drive systemic changes like school nutrition standards, regulation of food marketing, and public health funding.

6. Supports family-centred compassionate approaches

6. Supports family-centred compassionate approaches

By defining obesity as a disease, parents can more likely access help to support them in making healthy lifestyle changes without fear of judgement or blame.

Why Obesity Is Not a Choice

Suggesting obesity is caused by a lack of willpower or is a choice, leads to people oversimplifying the solution to obesity to ‘eat less, move more’. Although nutrition and physical activity are certainly key factors involved in the development of obesity, there are many root causes that often are interlinked.

The Obelisk project has an ambitious research programme to “cut the roots” to prevent childhood obesity. As explained by the World Obesity Federation, if we do not understand the deep-rooted causes, and only address them at a personal level, we will be unable to treat this disease and reduce obesity incidence.

Research shows that obesity has multiple, interconnected roots, including biological, social, and environmental factors. These include:

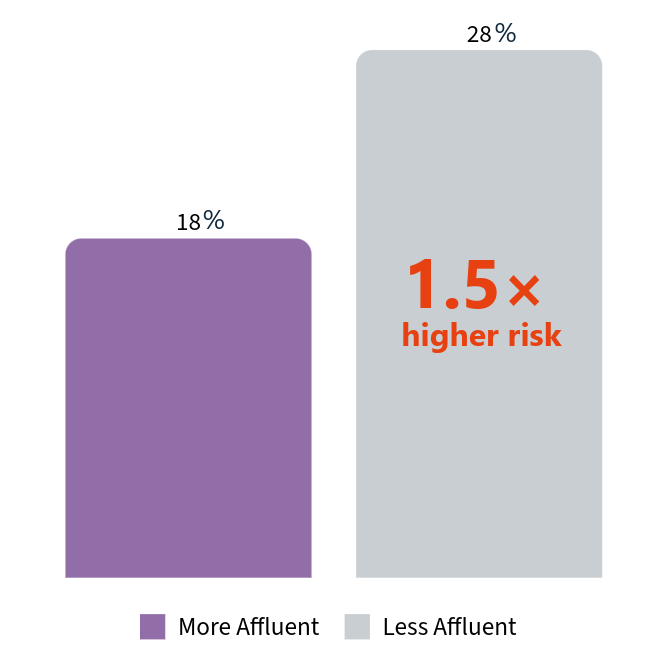

Socioeconomic factors: Adolescents from less affluent families are 1.5 times more likely to have overweight or obesity compared to their more affluent peers10.

Percentage of adolescents likely to have overweight or obesity

Genetics: The heritability of obesity is thought to be between 40-70%11.

Biology and intrauterine experiences: Early life influences, beginning in the womb, such as maternal health, nutrition, and growth patterns, can shape foetal metabolism and development via epigenetic changes in ways that affect obesity risk over the life course12.

Environmental factors: Across many parts of Europe, children are growing up in an obesogenic environment. Limited access to safe outdoor spaces, the widespread availability of fast and processed foods, and targeted marketing all contribute to increased risk, particularly among those already more vulnerable to developing obesity.

Unhealthy diets: Food affordability and changes in social norms contribute to a higher proportion of children eating a western-style diet, high in sugar, fat, energy and salt and low in fibre. Only 42.5% of children eat fresh fruit every day, meaning nearly 3 in 5 do not. Fewer than a quarter (22.6%) of children eat vegetables daily, so around 3 in 4 miss out13.

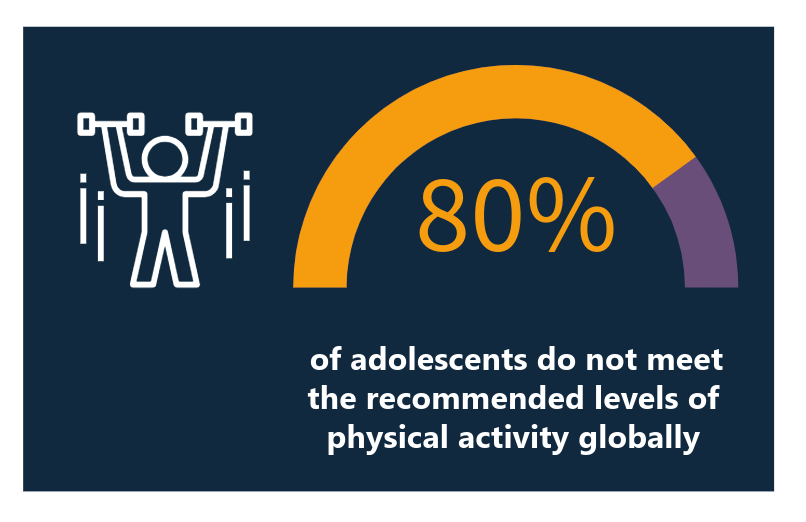

Lack of physical activity: Changes in social and cultural norms, such as increased screen time, environmental factors like access to safe outdoor spaces and affordability, can all lead to children doing less physical activity. 80% of adolescents do not meet the recommended levels of physical activity globally14.

Weight stigma: There is a common belief that social pressure or shame can encourage weight loss, however, children who experience weight stigma are more likely to gain additional weight and experience poorer well-being over time.

Moving Towards Solutions

Understanding obesity as a disease supports the move towards effective treatments and compassionate support for those living with the condition. This growing recognition also highlights the importance of prevention and early intervention - but more remains to be done. By educating professionals and society at large, we can promote health beyond simply focusing on numbers on the scale. A multi-sector approach, which includes healthcare, education, policy, and communities, is needed to create environments that reduce the risks so prevalent in daily life.

At Obelisk, we aim to share best practices and evidence-based policy guidelines to help prevent and treat childhood obesity. Our research explores the molecular mechanisms that influence the transition from normal weight to overweight or obesity during infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and investigates how different factors interact in this process. By uncovering these biological and environmental interactions, our work reinforces the understanding of obesity as a complex disease and will provide the evidence needed to design effective treatments and prevention strategies.

By recognising childhood obesity as a disease, we can replace stigma with support and give every child the chance of a healthier future.

References

- Brittanica Dictionary (2025) https://www.britannica.com/science/human-disease

- Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic

- NIH (1998). Expert Panel on the Identification, Treatment of Overweight, Obesity in Adults (US), National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, ... & Kidney Diseases (US). (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report(No. 98). National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

- Bray, G. A., Kim, K. K., Wilding, J. P., & World Obesity Federation. (2017). Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obesity reviews, 18(7), 715-723.

- WHO (2025) Obesity and Overweight. Accessed online 09.09.25 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight#

- EASO (2025) EASO response to the Lancet Commission Report on Obesity Diagnosis and Management. Accessed online 03.11.2025. https://easo.org/easo-response-to-the-lancet-commission-report-on-obesity-diagnosis-and-management/#

- Hampl, S. E., Hassink, S. G., Skinner, A. C., Armstrong, S. C., Barlow, S. E., Bolling, C. F., ... & Okechukwu, K. (2023). Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics, 151(2).

- NICE (2025) NICE Guideline NG246 Overweight and obesity management https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng246

- Farpour-Lambert, N. J., Baker, J. L., Hassapidou, M., Holm, J. C., Nowicka, P., O''Malley, G., & Weiss, R. (2015). Childhood obesity is a chronic disease demanding specific health care-a position statement from the Childhood Obesity Task Force (COTF) of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). Obesity facts, 8(5), 342-349

- WHO (2024) The inequality epidemic: low-income teens face higher risks of obesity, inactivity and poor diet. Accessed online 9.9.25 https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/23-05-2024-the-inequality-epidemic--low-income-teens-face-higher-risks-of-obesity--inactivity-and-poor-diet

- Masood, B., & Moorthy, M. (2023). Causes of obesity: a review. Clinical Medicine, 23(4), 284-291.

- Cristian A, Tarry-Adkins JL, Aiken CE. The Uterine Environment and Childhood Obesity Risk: Mechanisms and Predictions. Curr Nutr Rep. 2023 Sep;12(3):416-425. doi: 10.1007/s13668-023-00482-z. Epub 2023 Jun 20. PMID: 37338777; PMCID: PMC10444661.

- WHO (2021) How healthy are children’s eating habits? – WHO/Europe surveillance results. Accessed online 9.9.25 https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/03-03-2021-how-healthy-are-children-s-eating-habits-who-europe-surveillance-results#

- WHO (2024) Physical Activity. Accessed Online 29.9.2025 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity