The Hidden Impact of Weight Stigma on Children: What It Is and Why It Matters

The rise in obesity rates over the past few decades has created significant attention, with frequent media coverage highlighting this issue. However, the narrative around obesity can sometimes result in unintended harms, including the often-overlooked issue of weight stigma, which affects individuals across all ages—including children.

As part of the Obelisk research, we are conducting the Empowering Adolescents with Obesity to Unite for a Better Society (ADOBESIF) research trial. The study explores interventions aimed at supporting young people with obesity from low-income backgrounds, with a particular focus on improving self-esteem, reducing weight stigma through community-based approaches. Educating others and raising awareness of weight stigma is therefore a central component of the project, helping to inform more inclusive and effective strategies for adolescent health.

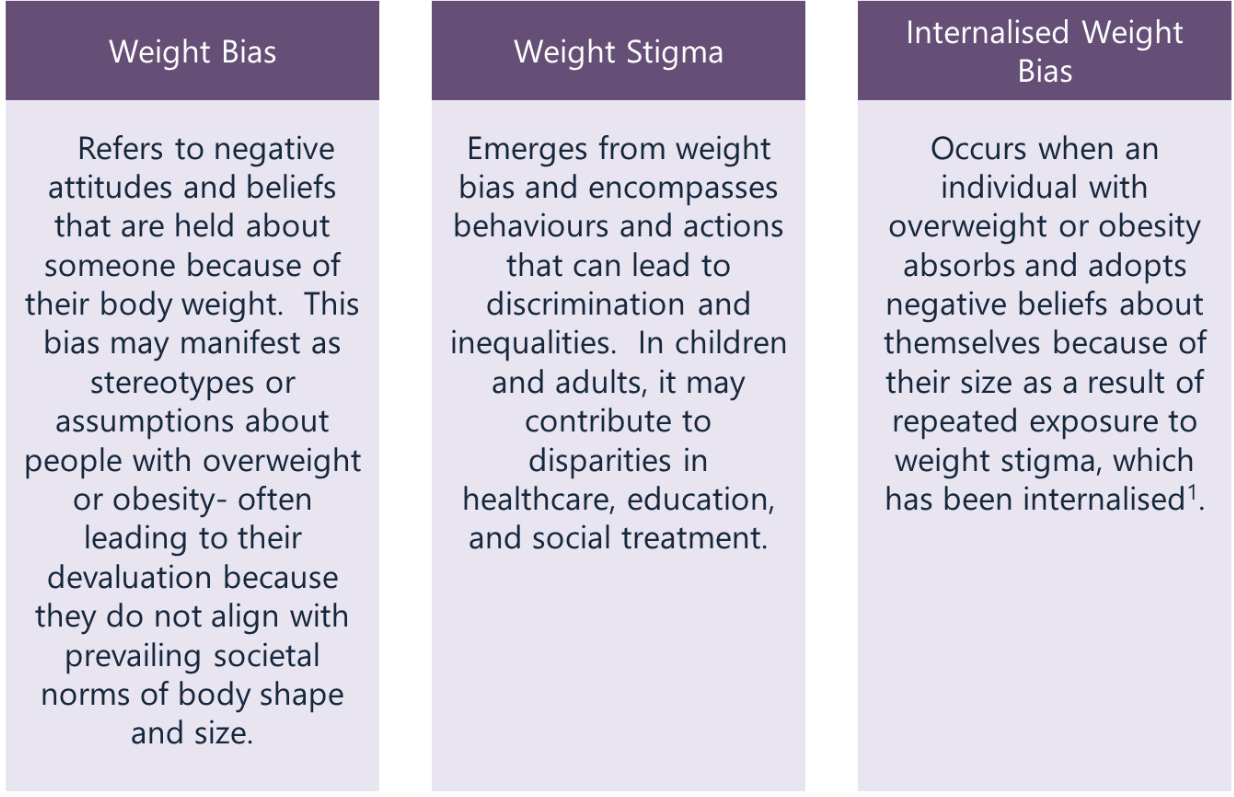

What is Weight Stigma?

Weight Stigma in Children

Much of the focus around childhood obesity is placed on potential health risks. However, children may face frequent weight stigma, which can also be damaging to their wellbeing. Weight stigma often stems from weight bias and assumptions that individuals with obesity are lazy, unmotivated and lack willpower or discipline2.

Children may experience this stigma in the form of social exclusion, teasing, or bullying. While peers are often the most common source, stigma can also arise from adults—including educators, healthcare professionals, and family members3. Research shows these experiences can impact a child’s physical, psychological, and behavioural wellbeing4.

There is a common belief that social pressure or shame can encourage weight loss. However, studies suggest this approach may have unintended consequences. For instance, children who experience weight stigma are more likely to gain additional weight over time5 and a meta-analysis has demonstrated a bi-directional relationship between weight stigma and weight status in children aged 6–18 years4.

Public Health Messaging and Policy

Historically, global obesity strategies have tended to focus on individual responsibility-emphasising messages such as “eat less and move more.” While well-intended, this framing can contribute to the perception that obesity results from personal failure, reinforcing stigma at a societal level.

For example, previous UK policy proposals suggested reducing benefits for individuals with obesity who were not perceived to be making sufficient health efforts. This illustrates how weight bias can exist at structural levels. A strong emphasis on individual responsibility within policy may risk overlooking environmental and societal drivers that contribute to obesity.

Research also indicates that some public health campaigns may inadvertently reinforce stigma6. One example is the 2011 “Strong4Life” campaign by Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, which featured billboards with children and slogans such as, “Stocky, chunky and chubby are still fat-Fat kids become fat adults”7. Evidence suggests that such campaigns risk discouraging engagement in health behaviours among the people they aim to support.

Moreover, individuals who feel stigmatised are more likely to report higher-calorie consumption, emotional eating, and reduced physical activity—all of which may contribute to further weight gain and negative health outcomes6.

Media Messaging

Media portrayals often amplify weight stigma through divisive language like “war on obesity” or pejorative terms such as “fatties.” In some cases, headlines such as “Fat shaming is the only way to beat obesity” have suggested that shame is a legitimate strategy to address obesity, despite research to the contrary.

There are guidelines, produced by experts in the field, that recommend the use of person-first terminology and avoidance of combative terms such as ‘war’8,9,10,11. However, media outlets often ignore them and opt for more provocative headlines with the aim of increasing engagement.

A study that looked at the portrait of obesity in UK newspapers found that they attribute obesity to controllable causes and that caricatured portrayals of overweight and obesity were evident12. And, in our project, we come across countless examples of negative and stigmatising images and language use by the media.

Studies show that how obesity is portrayed in the media can shape public attitudes. For instance, when negative, stereotypical images are used in neutral obesity-related reports, readers are more likely to express bias and make unfavourable assumptions. Conversely, positive or neutral images can foster more respectful perceptions6. Free, non-stigmatising image libraries are now available to support media and communications professionals with responsible visual representation from organisations such as the World Obesity Federation and the Rudd centre.

Stigma is also embedded in children’s entertainment. Research has found that characters with obesity in films and TV are frequently portrayed as lazy, greedy, or less desirable13,14. Adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to these portrayals during key periods of body image development due to content such as reality TV15.

Education

Teacher Attitudes

Weight bias can influence how teachers perceive and interact with students. Some research has found that teachers may hold lower academic and social expectations for children with overweight or obesity16 and view them as more burdensome to teach17. This bias may affect student self-esteem, classroom engagement, and academic achievement. In fact, children with higher body weight have been found to receive lower grades than peers with similar test scores18.

Bullying and School Absenteeism

Bullying is a major concern in schools and weight is one of the most common reasons children are targeted19. These negative stereotypes—linking weight to laziness or lack of discipline—often translate into verbal and physical harassment20.

Weight-based bullying has been associated with low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and long-term mental health risks. It also affects educational outcomes. Children who are bullied about their weight are significantly more likely to skip school or specific classes. A meta-analysis found that the odds of absenteeism were 27% and 54% higher among children with overweight and obesity, respectively21. One study found that those who experienced physical weight bullying were up to five times more likely to miss school22.

Can Weight Stigma Harm Health?

Weight stigma is linked to stress responses at the biological level. Individuals who experience discrimination have been shown to exhibit elevated cortisol levels, which may contribute to weight gain and a preference for energy-dense foods. Those who are stressed about their weight are also less likely to engage in physical activity due to their body image concerns and low self-esteem, impacting on their motivation.

Over time, repeated exposure to stigma may result in allostatic load-the cumulative strain on bodily systems from chronic stress. This can increase the risk of conditions such as inflammation and impaired glucose regulation. While research is ongoing, early findings suggest that weight stigma may contribute to physical health outcomes beyond psychological harm.

Maladaptive Eating Behaviours

A 2016 literature review found consistent associations between weight stigma and disordered eating behaviours. These included binge eating, emotional overeating, unhealthy weight control methods, and eating disorders23. These behaviours may contribute to the progression of obesity, highlighting why stigma-based approaches are unlikely to be effective public health strategies.

Inequalities

Weight stigma can also intersect with broader social inequalities. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds, ethnic minority groups, and communities already facing health disparities are more likely to experience higher rates of obesity and the associated stigma. This dual burden can affect educational attainment, future job opportunities, and healthcare access.

Without addressing these wider structural issues, public health policies risk exacerbating existing inequalities, despite aiming to reduce them.

How Does This Impact Policy/Public Health?

When planning public health interventions or campaigns related to childhood obesity, the way messages are framed plays a critical role in public engagement and behavioural outcomes. Evidence highlights how messaging approaches can either support or hinder health goals, depending on how they are delivered6.

Messages that imply individual blame, use judgmental language, or promote fear-based tactics may have unintended consequences-including disengagement, reduced motivation, or reinforcement of weight stigma. Conversely, messages that focus on adding positive behaviours—such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake or encouraging physical activity—tend to be received more favourably.

Public health strategies may be more effective when they:

- Emphasise health-enhancing behaviours rather than weight loss or appearance.

- Avoid stigmatising imagery—such as portraying people with obesity eating unhealthy food.

- Use inclusive, person-first language and avoid framing obesity as a moral failing.

Importantly, shifting the narrative from obesity as a matter of individual responsibility to a condition influenced by multiple, complex factors (e.g., environment, biology, social context) may reduce stigma and support more equitable, effective policy development.

Protective Factors: What Helps Reduce Weight Stigma?

While the impacts of weight stigma are significant, there are evidence-based approaches that can help reduce harm and build resilience—particularly when action is taken at school, family, and policy levels.

Here are some protective strategies to consider:

- In schools

-

- Implement anti-bullying policies that explicitly include weight-based bullying.

-

- Train educators to recognise and reduce weight bias in the classroom.

-

- Use weight-inclusive curricula that focus on health behaviours rather than weight status.

- In families and communities

-

- Model positive body image and avoid weight-related teasing or criticism at home.

-

- Encourage open dialogue that promotes body diversity and challenges stereotypes

-

- Foster peer support programmes that promote inclusion and resilience among children.

- In policy and public health

-

- Use non-stigmatising, health-focused messaging that avoids blame or fear-based language.

-

- Follow media guidelines that recommend respectful language and imagery.

-

- Consider legal protections that address weight-based discrimination in schools, healthcare, and employment.

These interventions, especially when implemented in combination, can help reduce the spread and impact of weight stigma across society and create more equitable, health-supporting environments for all children.

Conclusion

Weight stigma is a widespread issue with significant implications for children’s physical, mental, and social well-being. Though often unintended, certain messaging, educational environments, and media representations may contribute to this stigma and its associated harms.

The findings from the ADOBESIF trial will contribute valuable insight into how creative, inclusive interventions – such as group-based physical activity and stigma reduction initiatives- can support adolescents living with obesity. By addressing both health behaviours and the psychosocial impacts of stigma, the study aims to inform future approaches to obesity management that are not only effective but also socially empowering and equitable. Integrating this kind of evidence -whether in policy, public health, or practice- we can better support children and reduce the barriers that stigma creates. Shifting from weight-focused to health-focused approaches may offer a more effective and equitable path toward improving outcomes for all children, regardless of body size.

Useful Resources

European Association for the Study of Obesity | Person First Language Guide

World Obesity Federation | Healthy Voices Language Guidelines

European Coalition for People Living with Obesity | EPCO Image Bank

World Obesity Federation | Image Bank

References

- WHO (2017) Weight bias and obesity stigma: considerations for the WHO European Region. World Health Organisation 2017 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/353613/WHO-EURO-2017-5369-45134-64401-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J. (2020) The association between weight stigma and mental health: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020;21(1):e12935. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12935

- Puhl, R. M., & Latner, J. D. (2007). Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 557. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557

- Ma, L., Chu, M., Li, Y., Wu, Y., Yan, A. F., Johnson, B., & Wang, Y. (2021). Bidirectional relationships between weight stigma and pediatric obesity: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 22(6), e13178

- Jackson, S. E., Beeken, R. J., & Wardle, J. (2014). Perceived weight discrimination and changes in weight, waist circumference, and weight status. Obesity, 22(12), 2485-2488.

- Puhl, R. M., Luedicke, J., & Heuer, C. A. (2013). The stigmatizing effect of visual media portrayals of obese persons on public attitudes: does race or gender matter?. Journal of health communication, 18(7), 805–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.757393

- Keneally, M. (2012). ‘Mom, why am I fat?’ Controversy over shock anti-obesity ads featuring overweight children. Daily Mail.

- World Obesity Federation. Weight Stigma in the Media: The current use of imagery and language in the media. 2018. https://www.worl dobesity.org/what-we-do/our-policy-priorities/weight-stigma. 101

- Obesity Canada. Media Guidelines: Avoiding Weight Stigma & Discrimination. 2018. https://obesitycanada.ca/weight-bias/.

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Obesity A. The Current Landscape of Obesity Services Report from the APPG on Obesity. London: AllParty Parliamentary Group on Obesity; 2018. Parliament U, editor. https://obesityappg.com/inquiries.

- Rudd Center. Guidelines for Media Portrayals of Individuals Affected by Obesity https://uconnruddcenter.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2909/2020/07/MediaGuidelines_PortrayalObese.pdf

- Flint, S. W., Hudson, J., & Lavallee, D. (2016). The portrayal of obesity in UK national newspapers. Stigma and Health, 1(1), 16.

- Howard, J. B., Skinner, A. C., Ravanbakht, S. N., Brown, J. D., Perrin, A. J., Steiner, M. J., & Perrin, E. M. (2017). Obesogenic behavior and weight-based stigma in popular children’s movies, 2012 to 2015. Pediatrics, 140(6).

- Brown, A., Flint, S. W., & Batterham, R. L. (2022). Pervasiveness, impact and implications of weight stigma. EClinicalMedicine, 47.

- Karsay, K., & Schmuck, D. (2019). “Weak, sad, and lazy fatties”: adolescents’ explicit and implicit weight bias following exposure to weight loss reality TV shows. Media Psychology, 22(1), 60-81.

- Nutter, S., Ireland, A., Alberga, A.S. et al. Weight Bias in Educational Settings: a Systematic Review. Curr Obes Rep 8, 185–200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00330-8

- Wilson, S. M., Smith, A. W., & Wildman, B. G. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of youth with obesity in the classroom. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(4), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2015.1074054

- MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2013). Just as smart but not as successful: obese students obtain lower school grades but equivalent test scores to nonobese students. International Journal of Obesity, 37(1), 40-46.

- Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., O'brien, K., Luedicke, J., Forhan, M., & Danielsdottir, S. (2016). Cross‐national perspectives about weight‐based bullying in youth: nature, extent and remedies. Pediatric obesity, 11(4), 241-250.

- Pont, S. J., Puhl, R., Cook, S. R., & Slusser, W. (2017). Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics, 140(6).

- An, R., Yan, H., Shi, X., & Yang, Y. (2017). Childhood obesity and school absenteeism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity reviews, 18(12), 1412-1424.

- Lydecker, J. A., Winschel, J., Gilbert, K., & Cotter, E. W. (2023). School absenteeism and impairment associated with weight bullying. Journal of adolescence, 95(7), 1478-1487.

- Vartanian, L. R., & Porter, A. M. (2016). Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite, 105, 3–14