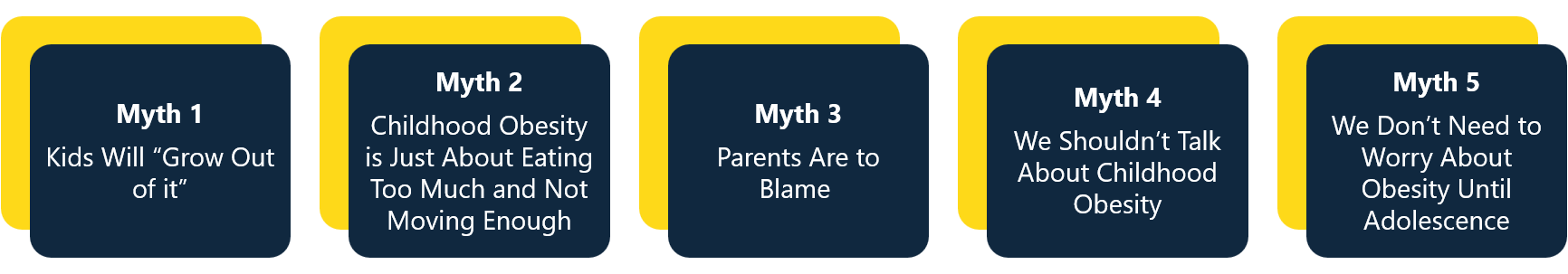

Five Myths About Childhood Obesity - and the Truth Behind Them

Childhood obesity is often discussed, yet misinformation and oversimplified narratives are common. This creates stigma and makes it harder to have open, productive conversations - or to find real solutions.

In this article, we unpack some of the most common myths about childhood obesity, explore the truths behind them, and share how the Obelisk project is working to shift the conversation toward more compassionate, evidence-based approaches.

Myth 1: Kids Will “Grow Out of it”

Temporary weight gain can indeed be a normal part of growth and development, especially before puberty. Many children experience phases where their weight increases, for example, before they have a growth spurt. This is not inherently a cause for concern, and in many cases, it's completely normal.

While some children may go through phases where they gain weight before a growth spurt, assuming all children will simply “grow out of” excess weight can be misleading. Research1 shows that persistent childhood obesity is unlikely to resolve without intentional, supportive changes. A child who is significantly above a healthy weight trajectory in middle childhood or adolescence is more likely to remain overweight into adulthood, which increases the risk of chronic health conditions. However, this doesn’t mean we should pathologise normal growth. The key is to look at overall patterns and well-being rather than single weight changes and to approach concerns with compassion, not blame. If a child’s weight continues to trend upward over time, it may signal a need for gentle support.

In Obelisk, one of our expected impacts is to increase the implementation of successful preventive and treatment programmes in clinics and communities, so that we can increase the percentage of children and adolescents with obesity who successfully receive support and recover from obesity before adulthood. Recognising when to intervene and provide families with appropriate support and treatment is key, and our research aims to address the scientific challenges that have previously hindered progress in childhood obesity research.

Myth 2: Childhood Obesity is Just About Eating Too Much and Not Moving Enough

Public health messages like “eat less and move more” have been widespread for several years. While mostly well-intentioned, this message places too much emphasis on personal responsibility, and research shows it’s largely ineffective in addressing childhood obesity.

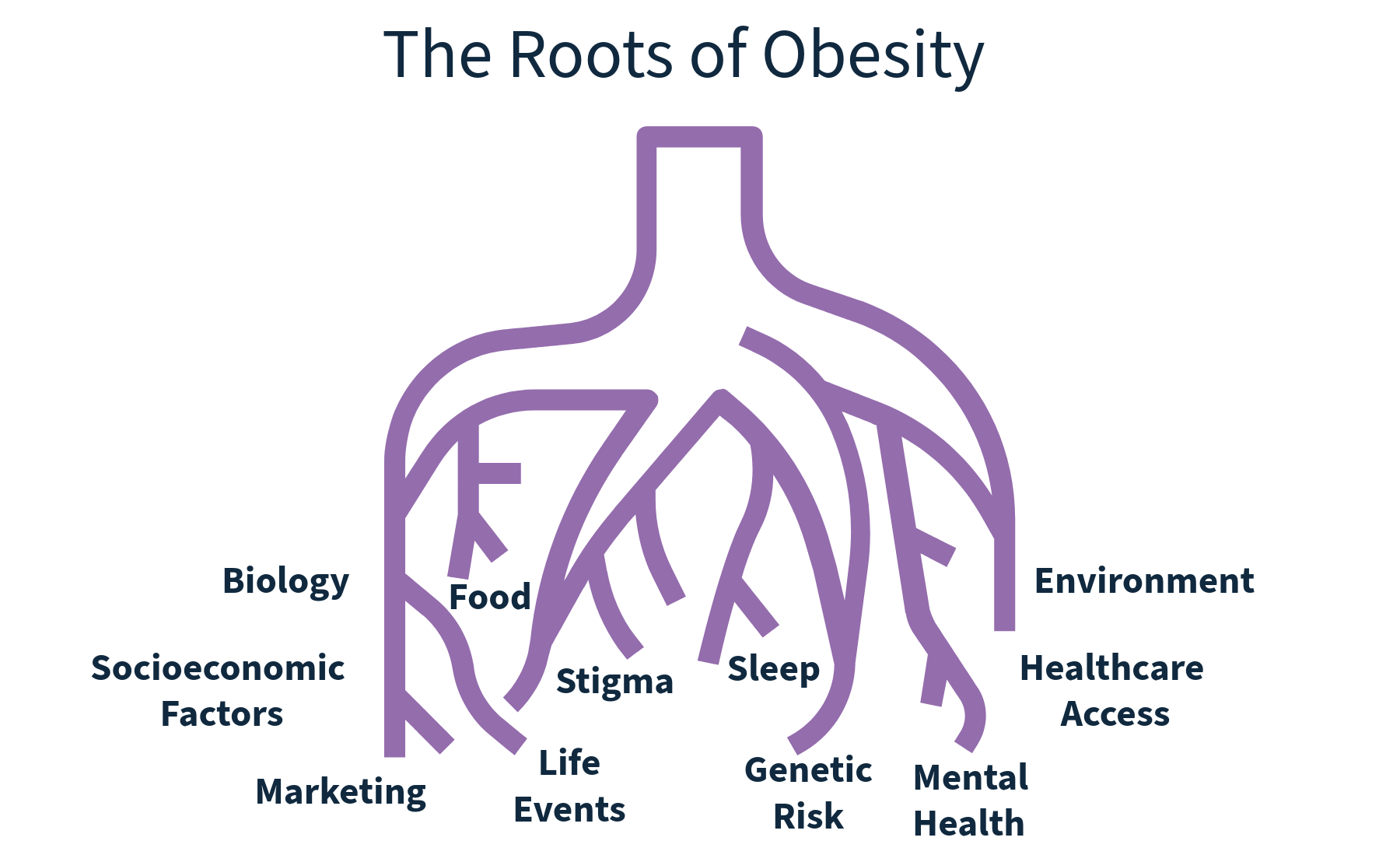

Diet and physical activity do matter. But a person’s weight is influenced by over 100 factors2, some within a family’s control, and many that are not. These include genetics, early life influences, environment, socioeconomics and social structures.

Obesity is not just a behavioural problem; it’s a complex, chronic disease. Reducing it to willpower alone is not only inaccurate, but it also risks blaming children and parents, which can lead to stigma and emotional harm.

When we look beyond simplistic slogans, we can create supportive, compassionate solutions that focus on overall well-being, not just weight.

In Obelisk, we aim to “cut the roots” of obesity by investigating the molecular mechanisms and other factors that contribute to its onset. We recognise that obesity is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, beyond just diet and exercise, and therefore the project aims to develop targeted interventions and treatments based on a better understanding of these underlying causes.

Myth 3: Parents Are to Blame

Blaming parents for childhood obesity is becoming increasingly widespread rhetoric, but in doing this, we are oversimplifying a complex, multifaceted issue.

With obesity disproportionately impacting those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, challenges such as limited access to healthy, affordable foods or safe spaces for physical activity can contribute to an increased risk of obesity. Stress and lack of social support will also impact both the parents’ and the child’s eating and physical activity habits.

Genetic makeup can influence a child's predisposition to obesity. One recent study3 found that parental feeding styles were responsive to children’s genetic predisposition to obesity. Children with higher body mass index scores received more parental food restriction, whereas children with lower scores faced greater pressure to eat. This research challenges the assumption that parental feeding styles are a primary driver of a child’s weight. Instead, child genetics seemed to evoke parental behaviour, meaning feeding strategies may reflect parents reacting to a child’s innate predisposition rather than shaping it. These associations held, even within non-identical twin pairs, showing that parents adjust feeding based on each child’s genetic tendencies, not merely shared family environment.

Whilst the vital role a parent plays in their child’s health and food intake must of course be acknowledged, a blame-based approach is unlikely to be effective and in fact can be detrimental, as this can lead to feelings of guilt and shame, potentially hindering positive behaviour changes. Parents may be living with obesity themselves and require support, and just as with children, an oversimplified message will not likely lead to positive change. Instead, a comprehensive, supportive, and multi-level approach is needed to create environments that promote healthy lifestyles for all children and support parents and families to make healthy choices.

One of our three trials within the Obelisk project is specifically looking at supporting families in low socioeconomic groups with adolescents – the Empowering Adolescents with Obesity to Unite for a Better Society - ADOBESIF Trial. This trial recognises the importance of supporting families and addressing social stigmas to empower them to make positive changes to support health.

Myth 4: We Shouldn’t Talk About Childhood Obesity

Talking about childhood obesity can be a challenge and should be approached with great care and compassion. But avoiding the topic altogether doesn’t protect children; it prevents us from creating meaningful, informed solutions.

Obesity is a complex issue that affects not just individual health, but also emotional well-being, social experiences, and long-term quality of life. By encouraging thoughtful, informed conversation, we can reduce stigma, deepen understanding, support more research, and influence broader changes in policy, environments, and systems.

Crucially, when speaking with or about children, the focus should never be on weight, appearance, or blame. Instead, conversations should centre on health-promoting habits, like joyful movement, good sleep, balanced nutrition, and emotional wellbeing, to help them thrive in supportive environments that nurture health at every level.

![]() 1. Silence can reinforce stigma

1. Silence can reinforce stigma

When the topic is avoided completely, it can send a message that it’s shameful, which increases internalised stigma in children and families already struggling.

![]() 2. Clear, respectful dialogue helps prevent misinformation

2. Clear, respectful dialogue helps prevent misinformation

Avoiding the topic leaves space for harmful myths or judgmental narratives to fill the gap.

![]() 3. Health professionals need guidance

3. Health professionals need guidance

Many healthcare providers want to support families but fear causing harm. Open, compassionate conversations- supported by clear guidance for health professionals- help build family-centred approaches.

![]() 4. Children are already absorbing messages about weight

4. Children are already absorbing messages about weight

Children live in a world filled with weight-focused media and peer pressure. Pretending weight issues don’t exist doesn’t shield them; it may leave them more vulnerable to shame or confusion.

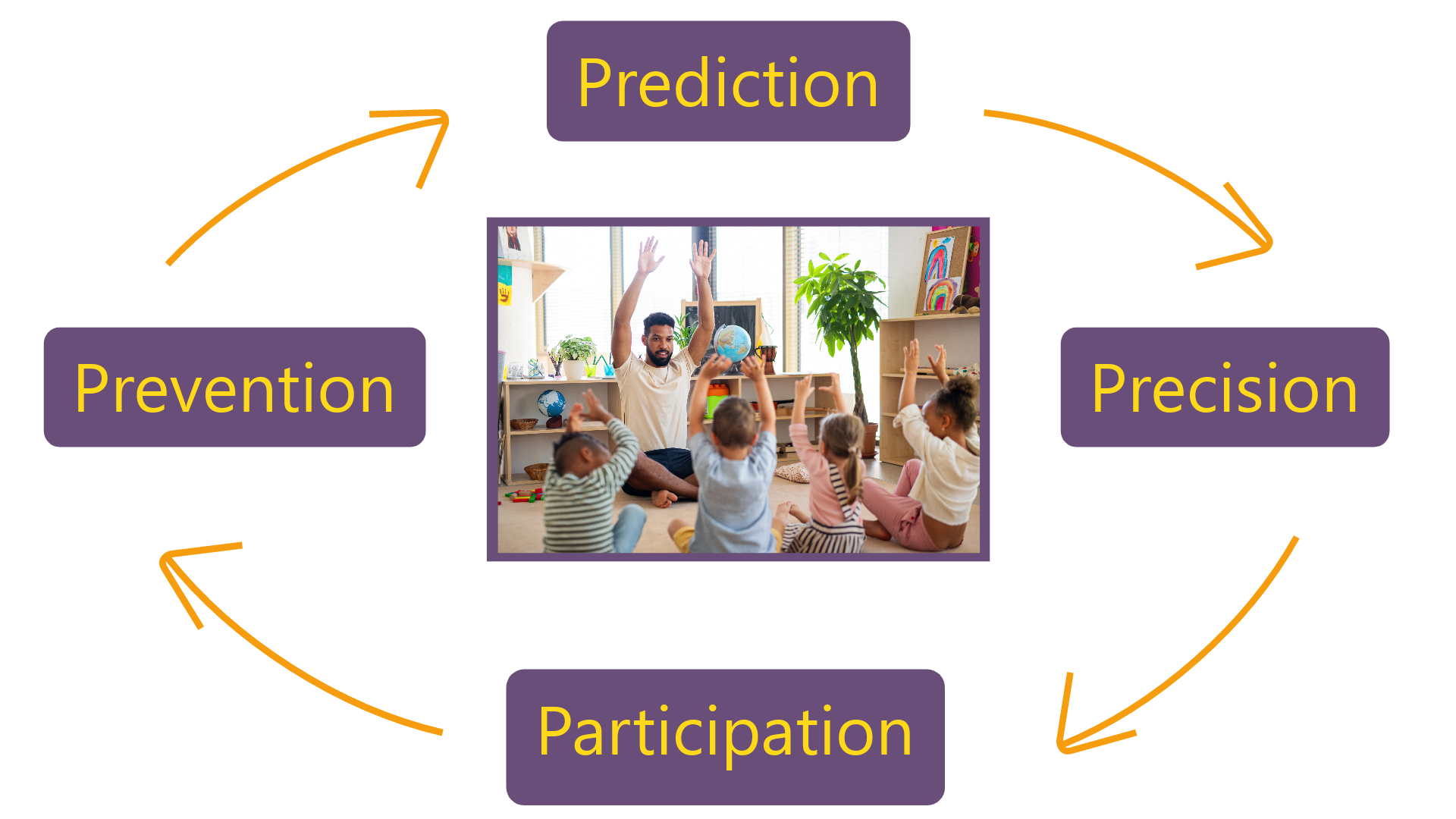

Obelisk is using a 4P’s approach which involves understanding, predicting, and preventing obesity in children and providing precision medicine for those affected, through active participation from all stakeholders, including families, scientific and medical communities, daycare centres, schools, policymakers, and industry. This requires open and ongoing conversations to drive social innovation and achieve successful outcomes, whilst raising awareness of childhood obesity and championing a compassionate non-stigmatising approach.

Myth 5: We Don’t Need to Worry About Obesity Until Adolescence

Early prevention is key. In fact, it starts before birth. Research highlights the critical role of the intrauterine environment - the conditions a foetus experiences in the womb - in shaping lifelong metabolic health. This process, known as metabolic programming, means that a child’s risk for obesity can be influenced before they are even born.

The first 1,000 days - from conception through the first two years of life - represent a critical window. During this time, a child’s growth patterns and weight trajectories begin to form through a combination of genetic and environmental factors4. Nutrition, stress, and other exposures during pregnancy and infancy can have long-term effects on a child’s body weight regulation.

Intervening in early childhood is significantly more effective than trying to reverse obesity during adolescence or adulthood. Prevention strategies that support all pregnant women, regardless of weight or health status, and extend through infancy and early childhood are essential for long-term impact5.

By supporting healthy development from the very start, we can reduce future risk and avoid the emotional and physical burden that comes from delayed intervention.

At Obelisk, we believe the most effective way to prevent a high prevalence of obesity throughout the life course is to avoid its development in children. Alongside this, promoting healthy weight maintenance during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood is also vital, requiring collective action to mitigate its impact on the health and well-being of our children and future generations.

References

- Simmonds, M., Llewellyn, A., Owen, C. G., & Woolacott, N. (2016). Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta‐Obesity reviews, 17(2), 95-107.

- Tackling Obesities: Future Choices Project Report 2nd Edition Government Office for Science (2007). Accessed 5.8.25 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a759da7e5274a4368298a4f/07-1184x-tackling-obesities-future-choices-report.pdf

- Selzam, S., McAdams, T. A., Coleman, J. R., Carnell, S., O’Reilly, P. F., Plomin, R., & Llewellyn, C. H. (2018). Evidence for gene-environment correlation in child feeding: Links between common genetic variation for BMI in children and parental feeding practices. PLoS genetics, 14(11), e1007757.

- The academy of medical sciences: Child’s weight for life shaped by first 1,000 days, report health experts (2025). Accessed 5.8.25 https://acmedsci.ac.uk/more/news/childs-weight-for-life-shaped-by-first-1000-days-report-health-experts

- Pérez-Muñoz, C., Carretero-Bravo, J., Ortega-Martín, E., Ramos-Fiol, B., Ferriz-Mas, B., & Díaz-Rodríguez, M. (2022). Interventions in the first 1000 days to prevent childhood obesity: a systematic review and quantitative content analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2367.