Healthy Eating Explained: Is It Truly Affordable?

The second episode of the Obelisk Project podcast explores the barriers to healthy eating and ways to support children in developing healthier eating habits. We were very happy to be joined by our expert, Professor Anita Morandi, a paediatrician who works as a partner in the Obelisk project at the University of Verona.

We have summarised the key discussion points below, but you can hear the full conversation here.

What Is Healthy Eating?

Forming healthy eating habits early in life is important, as patterns established in childhood often persist into adulthood and become harder to change over time. Yet many parents feel uncertain about what truly constitutes a healthy diet. Conflicting messages and scaremongering can make nutrition feel confusing and overwhelming, leaving families unsure of where to begin. Clear, straightforward guidance is therefore essential to help families adopt healthy eating, which is realistic and sustainable. Below, we outline some key nutritional concepts that are well established and supported by scientific evidence.

Children are Individual

Dietary reference values are set for children and are recommended to provide the energy and nutrients for physical growth and neurocognitive development.

Scientists know that children’s nutritional needs vary. Therefore, dietary reference values are set at a level that should meet the needs of almost all children (95%), instead of aiming for only the ‘average person’. This makes the guidelines a safe and reliable target for most families to follow, knowing that their child is very unlikely to miss out on essential nutrients.

Despite the recommendations covering almost everyone, no two children are the same. Growth patterns, appetite, activity levels, genetics, and health status can all influence what they need on any given day.

That’s why portion sizes are best seen as guides, not strict prescriptions. One day, a child might clear their plate and ask for seconds, while the next day they may eat only half, and that’s normal.

What Parents Can Do

- Think of guidelines as signposts pointing you in the right direction, rather than exacting rules. They provide general information for a balanced diet, not an exact checklist. Think about the overall dietary pattern needed to meet these guidelines rather than feeling every individual meal has to be ‘perfect’.

- Offer a variety of healthy foods regularly. This ensures that, over time, your child gets what they need.

- Trust their appetite cues. Most children naturally eat more when they need more and less when they don’t. If your child is growing well and seems healthy, that’s a strong sign they are getting the nutrition they need.

Overall Dietary Patterns Matter More Than Individual Foods

It’s common for certain foods to be labelled or demonised, which can leave parents thinking they should ban them altogether or feeling guilty if their child eats them. But building a balanced diet and a positive relationship with food isn’t about strict rules or removing foods entirely. Instead, the focus is on creating an overall dietary pattern that includes a wide variety of foods and aligns with nutrition guidelines. Within this, foods that are less nutrient-dense can still be enjoyed at times, but without replacing or overtaking the more nutrient-rich foods children need for growth and health.

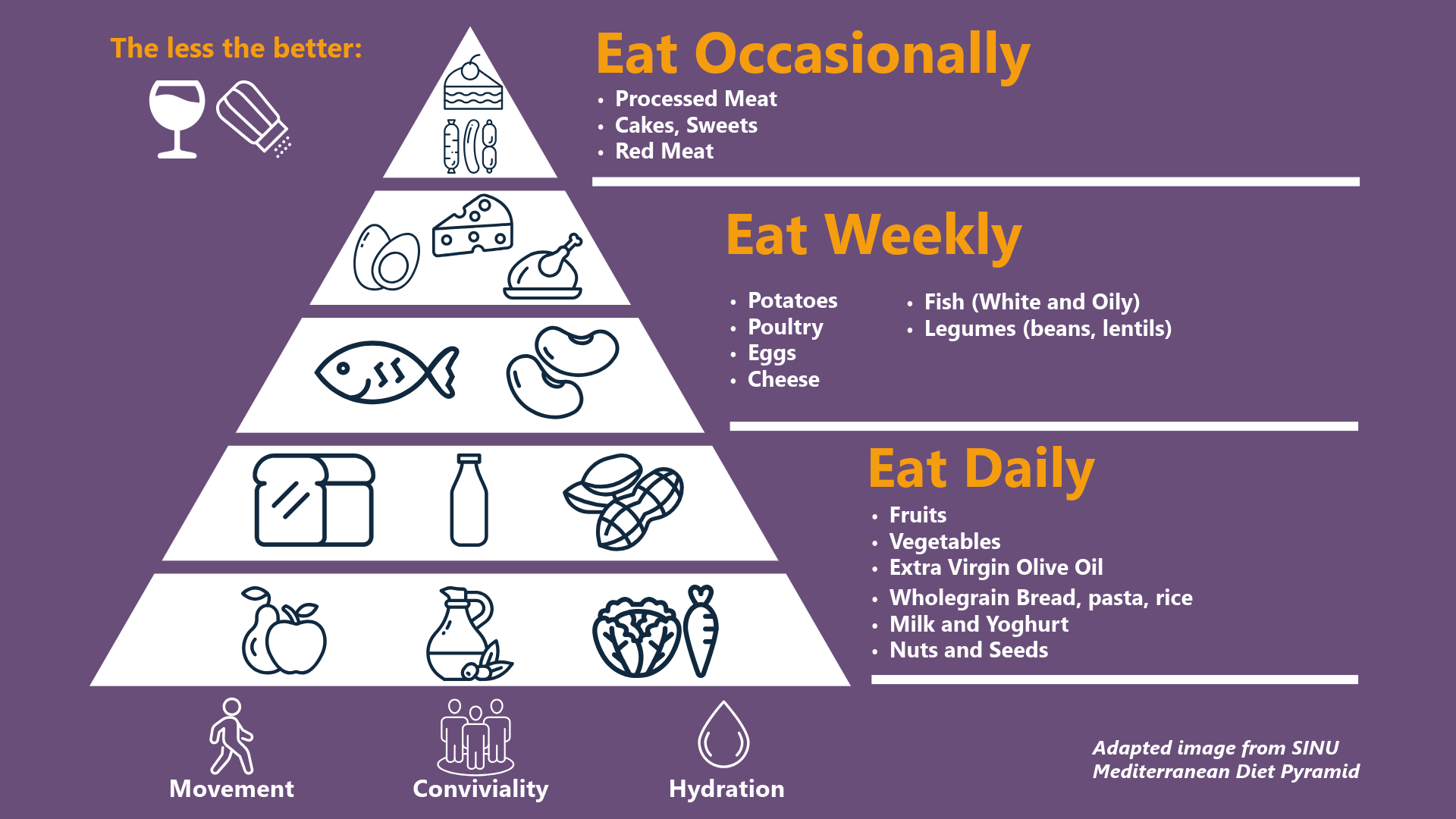

The Mediterranean dietary pattern is among those with the most evidence of long-term protective effects on health, so this can be useful for parents to consider when thinking about foods to include to improve overall healthfulness. This style of diet can be adapted to different local cultures.

A Mediterranean diet is defined by:

- Plenty of fruits and vegetables: Vegetables and fruits form the foundation of most meals.

- Whole Grains: Such as wholemeal bread, brown rice, and pasta.

- Legumes and Pulses: Beans, chickpeas, and lentils provide protein and fibre.

- Nuts and Seeds: A source of healthy fats and nutrients.

- Olive oil and other healthy fats: Increasing unsaturated fats, such as olive oil, and reducing saturated fats, such as butter.

- Moderate intake of fish, seafood and poultry: Especially oily fish, as this provides omega-3 fatty acids.

- Moderate amounts of dairy: Mostly as yoghurt, cheese and milk.

- Limited red and processed meat: Small amounts, eaten occasionally rather than daily.

- Minimal processed foods and added sugars: Sweets, pastries, fast foods and sugary drinks are occasional.

The degree of "Mediterranean-ness" of a child's diet can be easily and quickly assessed using version 2 of the KidMed score2, which consists of 16 simple yes/no questions, and this is a validated tool often used by researchers exploring the health of children’s diets.

Food Labelling Supports Informed Choices but Requires Clear Guidance

Since 2026, under the EU food information to consumers (FIC) regulation (1169/2011), packaged foods are required to display nutritional information on the back of the packet. Additionally, there is also voluntary front-of-pack information, such as the UK traffic light system or the European Nutri-score, giving a quick glance at the energy, fat, salt, and sugar content of a food. The effectiveness of food labelling for public health has yet to be confirmed by robust long-term epidemiological data, but it could likely have a positive impact on consumer awareness and their food choices.

When considering the prevention and management of obesity, it is important to recognise that nutrition information on packaging can sometimes be misunderstood. Without a clear understanding of energy balance and how to interpret labels, food claims may appear overly simplistic and even misleading. For example, some parents or caregivers may place too much emphasis on terms such as “light,” “low fat,” or “no added sugar,” assuming these products can be eaten without limit, while at the same time avoiding calorie-free drinks because of artificial sweeteners, yet permitting high-calorie alternatives that seem more “natural.” These patterns highlight the need for clearer guidance to support families in making informed decisions.

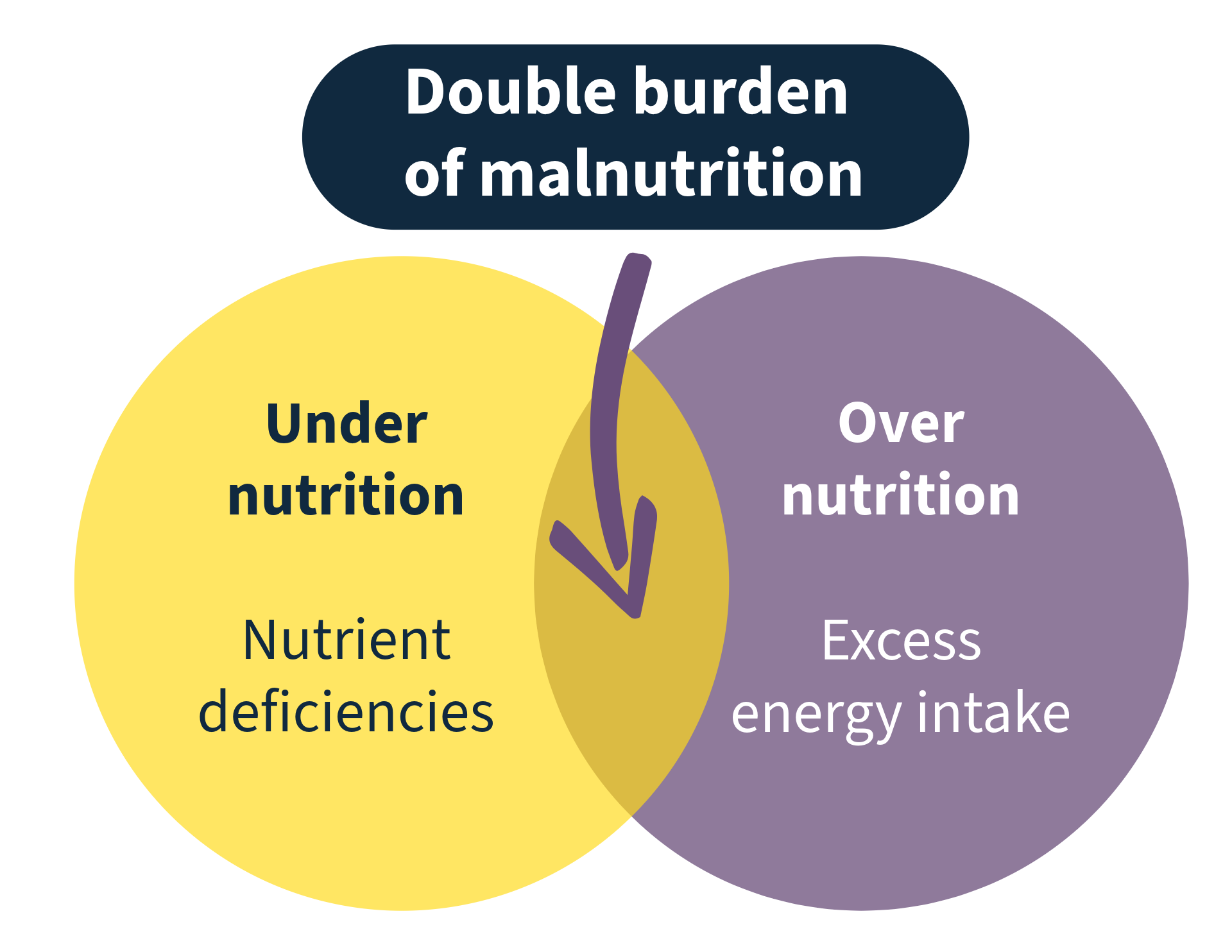

Obesity and Malnutrition Can Coexist

A healthy diet is about much more than calories: we need a variety of nutrient-dense foods to provide the vitamins and minerals essential for good health. It is not always recognised that a person can be living with obesity while still being malnourished. This is often described as the double burden of malnutrition - the simultaneous presence of both undernutrition and overnutrition. This perspective reminds us to consider dietary patterns as more than just the balance of calories needed to meet energy requirements.

For example, a child may consume more energy than they need but still fall short on key micronutrients such as iron, vitamin D, or iodine3. This is known as hidden hunger, because high energy intake can mask underlying nutrient gaps. Recognising hidden hunger underlines the importance of nutrient quality, not just quantity, in children’s diets.

How Affordable Is Healthy Eating?

The cost of a healthy diet has been on the rise in recent years.

The surge in the cost of a healthy diet reflects an overall rise in food inflation that hit every region following global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, wars and

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study4, highlights the rise in unhealthy eating habits, rising rates of overweight and obesity, and low levels of physical activity among young people, with those from less affluent families disproportionately affected.

There are several reasons why economics influences a family’s food choices:

- Processed foods are often cheaper, are quick to prepare when time is short and often have a longer shelf life or are stored in a freezer. This can be more economical as nothing is wasted, which is often a problem with fresh foods like fruits and vegetables.

- Families may be reliant on food banks, which may provide less healthy foods and remove the ability to choose, and can be less consistent at meeting nutritional requirements.

- Parents may not have the knowledge required to cook foods from scratch within a budget; this is not something that forms part of our education at school.

- Processed foods are often quick to prepare and therefore lower energy use.

However, there is evidence to suggest that this issue is more complex than a simple correlation between low income and reduced access to healthy food.

Research from the HELENA study5, which explored the link between socioeconomic status (SES) and diet quality in European adolescents, found that several factors contribute to this association beyond cost alone. These include the regular availability of soft drinks at home, limited availability of fruits and vegetables, fewer parental food rules, and lower levels of cooking skills. Such factors were more commonly observed in families with lower educational, occupational, or income levels and represent important targets for educational and public health strategies.

In 2024, the World Health Organization published a guideline on fiscal policies6 to support healthy diets, highlighting both taxation and subsidies as viable policy options. These measures are important for creating food environments that make healthier choices easier. For example, ‘sugar taxes’ have been implemented in many countries and can help shift behaviours. However, it is crucial to balance this with affordability, ensuring that the financial burden does not fall disproportionately on families already struggling. Government assistance programmes, such as subsidies for fruits and vegetables, free school meals, and breakfast clubs, also play a vital role in making nutritious food more accessible and affordable.

While it is often argued that healthy eating can be affordable in theory, in practice it requires specific knowledge, planning, and time. These resources are not equally available to everyone and can create significant barriers, making the issue far more complex than income alone. Addressing these challenges means considering how best to reduce barriers and support people in understanding and applying healthy eating recommendations in ways that are realistic for their circumstances.

Understanding the Challenges Around Children’s Healthy Eating

Most parents want their children to have healthy diets, but getting them to choose fruits and vegetables over snacks and sweets can be challenging.

Specific challenges to children eating healthily include:

- Selective eating in childhood: Many children naturally go through phases of being more selective with foods as part of their development, which can make it harder to achieve dietary variety, as this can limit exposure to a wide range of nutrients for that time.

- Screen time and advertising: Exposure to media and marketing strongly shapes children’s food preferences, often encouraging choices that are less aligned with healthy eating.

- Cultural and family influences: Children’s eating patterns are strongly shaped by family routines, traditions, and cultural food practices.

Ways Parents Can Support Healthy Eating Habits

- Talk about what food does, not whether it’s “good” or “bad.” Instead of labelling foods as healthy/unhealthy, explain their function in a child-friendly way, for example, “this food gives you energy to run fast” or “this food helps your bones grow strong.” Avoid forcing children to eat certain foods in the name of “health.”

- Avoid using food as punishment or reward. This can create unhelpful emotional associations with eating.

- Make nutritious foods easy to access. For example, keep a fruit bowl on the table at a child’s eye level.

- Normalise a wide range of foods. Serve vegetables, fruit, and other nutrient-rich foods as part of everyday meals, rather than something to “get through” before dessert.

- Share the same meals as a family. Allow children to choose what and how much to eat from what’s on the table. Remember it can take 15–20 exposures before a child accepts a new food. Keep offering without pressure and celebrate small steps like trying a bite.

- Model positive eating habits. Children learn by watching others. Eating together regularly can encourage positive attitudes to food.

- Involve children in food preparation. Cooking together and learning where food comes from can make children more interested in trying new foods.

- Make food appealing. Present meals with colour, variety, and fun shapes to capture children’s interest.

How is Obelisk Supporting Healthy Eating and Food Affordability to Prevent and Treat Childhood Obesity?

Our research is committed to improving children’s health by looking beyond individual choices to the wider factors that shape eating habits. By addressing the barriers highlighted in this article - from food environments and socioeconomic influences to cultural and family contexts - we aim to support healthier futures for all children.

To tackle these challenges, Obelisk is leading two clinical trials in this area. Find out more about these here.

For the full conversation on this topic, listen to the podcast here.